The cave paintings at Lascaux

Context

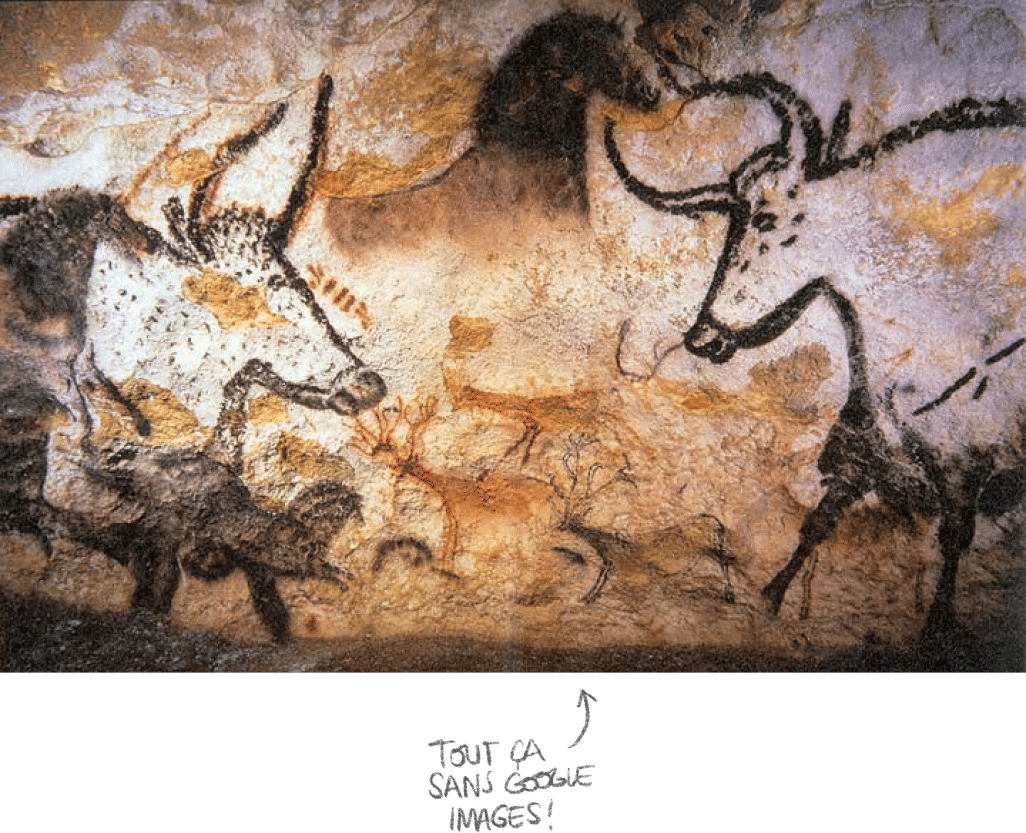

The cave paintings in the Lascaux cave, discovered in 1940 in the Dordogne, crystallise, as far as we know, the moment when drawing itself was invented. Around 17,000 years ago, hunter-gatherers of the Palaeolithic period simplified the world for the first time with sketches. Without any other previous drawings to serve as a reference, this first one must have required an extraordinary ability for abstraction. These drawings were not mere decorations; they served to convey knowledge, myths, and beliefs. They mark an essential stage in the history of our species, when images became a tool for explaining and preserving a collective vision of the world.

An explanation drawn out

The Lascaux frescoes are a striking example of universality: and we are still able to understand them today (if only in the first degree). In practical terms, they form a mental map of the relationship between humans and their environment. The exaggerated proportions, dynamic movements, and juxtaposition of figures seem to tell complex stories. Some researchers believe they explain animal behaviour, hunting cycles or survival rituals.

The spatial arrangement of the figures — some animals dominating the central wall, others relegated to the sides — contextualises their perceived importance. This primitive visual language offers an overview of the concerns and beliefs of our ancestors, and anchors their knowledge in a (very) durable form.